At the time of my matriculation into the first grade at East Ward Elementary in Mount Pleasant, Texas on September 6, 1949, my teacher Miss Sims was more than sixty-years old and had already been teaching there for twenty-eight years. Born in Victorian times, she was the classic old maid schoolteacher—gray hair in a tight bun, stern countenance, and no-nonsense attitude—and she expected her students to color within the lines, behave impeccably, and obey her demands instantly and without question. She was especially harsh toward the boys in the class, not comprehending that their unique gifts were sometimes cloaked in physical activity, impulsiveness, and spontaneity.

Miss Sims (as do some teachers today) considered boys a breed apart: wild, disobedient, and academically slow. Thus she believed she had moral authority to be merciless, overbearing, and controlling with boys in an attempt to tame them and squeeze them into the confining and restrictive ideal of the time—obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.

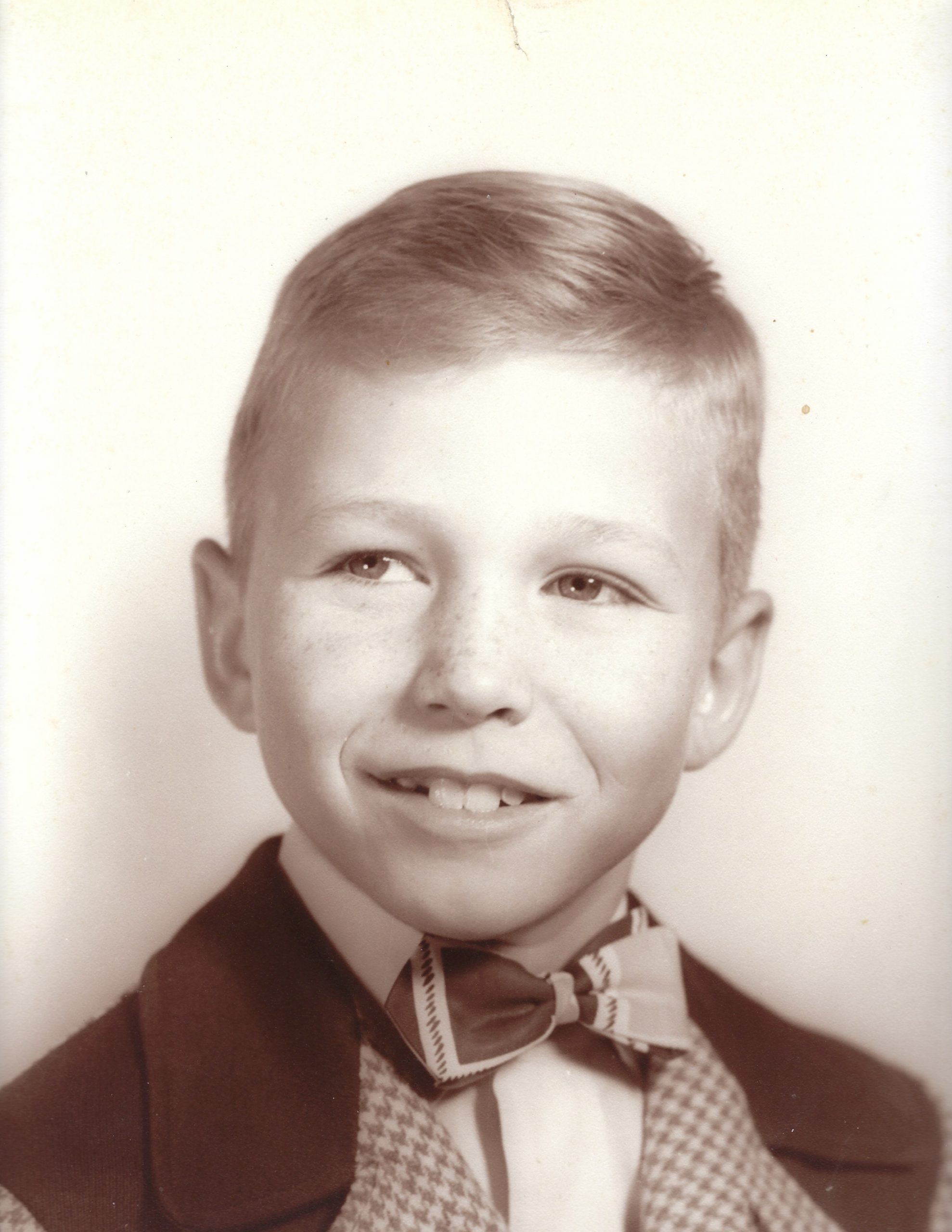

I arrived for my first day of school self-conscious and apprehensive. There were so many new faces (twenty or so), and Miss Sims’ foreboding manner scared the crap out of me. “That old woman really looks mean,” I thought. “I want to get out of here!”

At the beginning of the school day, Mom stayed in the meticulous little classroom for twenty or thirty minutes, as did some of the other mothers, mostly to help settle the nerves of us newcomers. She’d made me what was to become my customary lunch—a cheese sandwich with lettuce and mayonnaise on white bread, wrapped in wax paper, along with an apple—and placed it in a well-used brown paper bag with my name printed on it. When it was time for her to leave, Mom handed the bag to me and, with a light kiss and a hug, was gone.

When lunchtime rolled around, we began lining up to march single file to the cafeteria, but I couldn’t find my lunch anywhere. I was frightened and wanted to cry, but I stuffed my feelings down. I was afraid I’d have nothing to eat and that the other kids would mock me. Treated like a charity case, I was given a school lunch, unfamiliar stuff that I tentatively picked at as the boisterous throng around me gobbled down the chipped beef on toast, later to be renamed shit-on-a-shingle.

Upon arriving back in the classroom, one of my fellow students guffawed, “There’s his lunch under his desk. He was upset about nothing.” Again, I tamped down my trepidation: “If I cry they’ll think I’m a sissy. I can’t show them I’m scared.”

After that I settled in for the long haul, determined to make the best of a situation that truly sucked. I endeavored to behave and live up to Miss Sims’ perplexing expectations and persnickety directives, though frequently I didn’t.

One day we were given a sheet of paper with a black and white outline of a nature scene—trees, flowers, the sun, and so on—and instructed to color the scene, not only within the lines, but in the prescribed colors as well. I was coloring along using all the crayons in my trusty Crayola eight-pack, exceedingly happy with my creation, when Miss Sims walked by and spotted my handiwork. “Bruce, you’re not using the right colors! Don’t you know how to follow directions?” My heart sank; I slumped into my desk chair, embarrassed and ashamed: “I must be stupid. I’ve messed up. I’ll never get it right.”

And then, Valentine’s Day: I had a little crush on Ellen, a cute brunette with lovely features, a kind of miniature Annette Funicello (on whom later I’d also have a crush). I’d been ill but was finally well enough to join my class for our Valentine’s Day celebration. When I got to school I passed out some Valentines to my classmates, then I shyly gave Ellen a bright red plastic bracelet attached to a greeting card. Looking like she wanted to run, Ellen avoided my eyes, mumbled “Thanks” and halfheartedly accepted my gift. There was considerable snickering from my classmates, and one boy said, “Hey, Bruce likes Ellen! Haw, haw!” The perturbed expression on her face, her indifferent acceptance of the treasure I’d naively presented to her, and the outburst of laughter from what seemed like the whole class cut deeply and my little heart ached. “Dang, I’m a real jerk,” I thought. “I’ll never do that again.” I withdrew deep inside myself, never again to approach Ellen or any of the other girls in my class. After that humiliation I kept my feelings to myself and my cards (Valentines or otherwise) close to my chest.

The pièce de résistance during my first year of school came on a rainy winter day when we were forced to have recess in our classroom instead of on the playground. I was in one of two groups of boys who were each building towers out of blocks. Our endeavors quickly turned into a competition to see who could build the highest tower, and we were neck and neck, with only one box of blocks remaining. I raced for that box, as did Jimmy from the other team. As we scampered toward the bookcase where the last box of blocks sat, we collided with one another and inadvertently knocked over a potted plant. I stared in disbelief as the pot fell, seemingly in slow motion, then shattered on the floor with soil and plant spilling indiscriminately around the broken pieces of pottery. “Oh, my gosh,” I thought. “She’s going to kill me.”

Miss Sims was furious. She grabbed me and Jimmy and dragged us to the principal’s office. Once there, she opened a closet door and shoved us inside. “Let this be a lesson to you wild boys,” she called as she slammed the door shut.

So there we were in a tiny closet, no light, just me and Jimmy and a lot of school supplies. Jimmy started to weep, and I tried to console him: “At least we’re getting to miss reading more Dick and Jane,” I said. But Jimmy said nothing and continued to whimper. I was scared too. Like it or not, Miss Sims and the other teachers were in control of us during the school day. I told myself I had to stand tall like the Lone Ranger or Roy Rogers or my pal Marvin, that I should force my anxiety and fear down, all to no avail.

After an interminable period of time (probably fifteen or twenty minutes), we were released from our captivity and returned to the classroom. Jimmy and I entered the room filled with shame, heads hung low as we lurched back to our desks.

Annie Sims taught at East Ward Elementary from 1921 until her retirement in 1957. In 1958 the school was renamed Annie Sims Elementary in her honor.

# # #

Postscript: As I’ve worked on my memoir, what’s become a massive act of self-interrogation, I’ve realized that my disconcerting experiences during the first grade that I’ve described above profoundly influenced my attitude about school for the remainder of my classroom days. More details to come!