A largely overlooked book by Wilma Dykeman and her husband James Stokely made a powerful plea for racial justice in 1957.

When my wife Shonnie and I moved to Asheville from Austin in 1997, I was familiar with the names of native son Thomas Wolfe, O. Henry (who, along with Wolfe, is buried in the Riverside Cemetery), and of course, Carl Sandburg and his Flat Rock home Connemara. But somehow I’d never heard of Wilma Dykeman. However, it didn’t take long before I came across a copy of The French Broad, a book I consider essential reading for anyone living in this part of the world. Not only does the The French Broad bring forth the history surrounding the river that makes its way through western North Carolina, seven years before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Dykeman made a prescient and compelling argument for the care and nurturing of our natural environment.

Nowadays in Asheville, you can’t go long without hearing Wilma Dykeman’s name. A central section of the French Broad River Greenway system is named in her honor. Her family home in Beaverdam now accommodates the University of North Carolina Asheville’s Wilma Dykeman Writer-in-Residence program. And the programs, events, and workshops of the Wilma Dykeman Legacy help perpetuate her legacy as a pioneering advocate of Appalachian Studies, civil rights, fiction and poetry, history, journalism, public speaking, women’s rights, and the critical necessity for us to respect our environment.

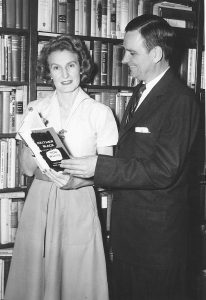

However, until I ran across a copy of Neither Black Nor White (©1957) at a used book store a few years ago, I was unaware of Dykeman’s and her husband James Stokely’s resolute support for racial equality when this was clearly a minority sentiment in the South. The research for their book began just a few years after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices issued a unanimous verdict against racial segregation in public schools. The couple drove throughout the South speaking with a broad range of men and women, ranging from staunch segregationists to ardent integrationists, both Black and White. During their travels, Dykeman and Stokely time and again encountered fierce resistance to the Court’s desegregation ruling, many proclaiming that it would never be accepted in southern states. Out of their experiences, the couple observed, “Part of the problem of the South may be summed up in the realization that for generations we were a land committed to two races, one crop (cotton) and no change.”

Full disclosure: I play handball at the Asheville downtown Y a couple of days each week with Jim Stokely, Wilma and James’ son. One morning over coffee on the banks of the French Broad River, I spoke with Jim about his parents’ early support of civil rights.

“They were for integration at a time when it was definitely not accepted in the South,” Jim said, “and while they had their supporters, many in North Carolina considered their views to be radical. Nonetheless, Neither Black Nor White received positive reviews across the country, including a few newspapers in North Carolina, and won the Sidney Hillman Award as the best book of the year on world peace, race relations and civil liberties. However, the thrust of the book was out of step with the generally conservative culture of Raleigh, Winston-Salem, and other state centers of influence. And as a result, invitations for Wilma to speak fell off, and some former friends drifted away.”

In response to Brown v. Board of Education, in 1956 Southern members of Congress created the Southern Manifesto that adamantly opposed racial integration by any legal means necessary and argued for the doctrine of “separate but equal schools.” The document was signed by nineteen U.S. Senators and eighty-two Representatives from states of the former Confederacy, including North Carolina Senators Sam Ervin and Kerr Scott and most of the state’s Representatives. However, Tennessee’s Senators Al Gore, Sr. and Estes Kefauver along with a majority of Tennessee’s members of the House rejected the document and refused to sign it. Because of this, Dykeman and Stokely made a conscious choice to live in Tennessee. Still close to the French Broad River, they visited Dykeman’s mother at her Asheville home frequently.

“My parents took a courageous stand when most Southerners vehemently opposed any movement toward racial justice however slight,” said Jim Stokely. “They believed that ignoring the cries for justice from Black men and women would only exacerbate the problem and kick the ball down the road. As they stated in their book, ‘Like thorn bushes in a Tennessee hillside pasture when they are hastily cut down year after year but are not grubbed out by the roots, so these issues, never squarely met and solved, sprout back to plague us again and again.’ So here we are half a century later apparently unable to even decide whether to teach the truth about slavery in our public schools. Regardless I can still do my part here in Asheville and hopefully live up to my parents’ legacy.”

For more information on the Wilma Dykeman Legacy and their work in our community, visit http://wilmadykemanlegacy.org/home.html.