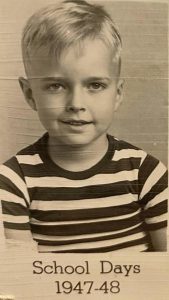

My longtime friend Stewart Horn was born on July 3, 1942, and he lived a long and full life. He died on September 23, 2022.

I first met Stewart when, at the age of 12, I joined Boy Scout Troop 112 in Tullahoma, Tennessee. Stewart, Pete Mulloney, Fred Hollenback, Chuck Millard, Carlton Sivells, Bucky Jackson and I, among others, looked forward to the fall and spring Camporees with great anticipation. At these campouts, troops from around the region met for fellowship and to compete for “Best Campsite” and other camping awards. To be out in the forest on our own for several days was a true godsend at the time. Through these experiences we learned that we could take care of ourselves and compete on an even footing with other boys our age. In that environment we began to feel more at home in the wilderness and more at home with ourselves.

I don’t recall consciously choosing Stewart as my role model, but there’s no doubt that he was. When Stewart achieved the highest rank in scouting—Eagle Scout—I followed in his footsteps. And when he was initiated into the Order of the Arrow, I was too.

While recalling our days in the Scouts, I thought of the Boy Scout Law, which, after more than half a century, I can still recite from memory:

A scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.

As I reflected, it became clear to me that Stewart did his best to follow those admonitions throughout his life and inspired me and others to endeavor to do so as well.

Most of the boys in Troop 112, including Stewart and me, went to Camp Boxwell for a week or two each summer along with scouts from other troops throughout middle Tennessee. Camp Boxwell was located near Rock Island on the Caney Fork River outside of McMinnville, Tennessee and consisted of six campsites, each equipped with a circle of a few dozen canvas-walled tents with wooden floors.

Our favorite activity at Camp Boxwell was the shooting range, where we shot .22 rifles at targets, hoping to win National Rifle Association marksmanship awards. Though we occasionally did some arts and crafts, our next favorite activity was the snack bar, where you could buy ice cream sandwiches, candy bars and Cokes. A limited amount of spending money was the only thing that held our sweet tooths in check during those glorious weeks.

Of course, juvenile high jinks were part of the camp experience too. One summer night Stewart and I, along with two others, picked up Carlton Sivells’ bunk and carried him from his tent into the surrounding forest, where he later awoke with quite a start. Then there was the timeless camp tradition known as the “hand in the bucket of warm water gambit.” The idea was that immersing a sleeping camper’s hand in warm water would induce him to urinate while in his sleeping bag. I don’t recall that these efforts were ever successful, but we persevered summer after summer.

Onward For God And My Country

In July 1957, the National Boy Scout Jamboree was held in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and Scouts from our troop, including Stewart and me, joined more than 50,000 others in the festivities. “Onward For God And My Country” was the theme, but left to our own devices for the most part, we were more into tomfoolery than God or country.

At the end of the Jamboree, we took a side trip to New York City, an amazing experience for our small-town entourage. We threw paper airplanes from the top of the Empire State Building, saw the Statue of Liberty, toured the Museum of Natural History, and ate hot dogs and pretzels from the ubiquitous food carts.

Boundary Waters Canoe Trip

The most exciting adventure we ever undertook as Scouts was the 1958 Boundary Waters Canoe Trip on the Minnesota-Canadian border. I was fifteen and Stewart was sixteen, both pretty seasoned campers. But nothing could have prepared us for the ten days in pristine wilderness, during which we paddled long distances each day, portaged across land from one lake to another, stretched our food supplies to make them last, and of necessity, supplemented our diet with fish we caught along the way. We also had to fight off swarms of huge mosquitoes at dusk that necessitated early bedtimes behind the protection of the mosquito netting of our tents.

Our trip leader paddled solo, I was in a canoe with Stewart and Fred Hollenback, and there were five other canoes with three Scouts each. As usual, Stewart, Fred and I were fooling around, and we fell far behind. Failing to sense the urgency of the situation, we continued to mosey along, eventually losing sight of the rest of our group. We desperately picked up our pace, all three of us paddling at once (usually the guy in the middle rested), but to no avail. To this day I’m not sure how we found the rest of our party, but after night had fallen, we spotted a campfire on a bank up ahead. We called out and were greeted in return with hoots and catcalls. Dinner had been prepared and devoured a couple of hours before our arrival, so we went to bed with bellies that were empty and minds that were filled with the exigencies of accountability in the wilderness.

In the days that followed we kept up with and sometimes led the pack, paddling with grit and determination along with a measure of good humor, frequently accidentally splashing other canoeists as we passed them. To the chagrin of our trip leader, who was something of a purist, we rigged up a sail with one of our ponchos and, with no paddling at all, crossed the open lakes at high speed propelled by the wind alone.

I don’t know that this trip turned boys into men, but it was an adventure that tested the wit, intellect, willpower and wisdom of all who participated in the Boundary Waters adventure. We’d come to a wild place that was, in many ways, unfamiliar, but that at some level, each of us recognized as home.

At the conclusion of the canoe trip, we rode on our bus from Ely, Minnesota, to Chicago, where we spent two exciting days entirely on our own. Ready for the pleasures of a big city after our time in the wilderness, we ate our first pizza ever and saw every Bridgette Bardot movie in town, And God Created Woman and The Night Heaven Fell among them. We returned to Tullahoma with a greater awareness of the world beyond the city limits of our little hometown, an enhanced sense of self-sufficiency, a stronger awareness of a primal attraction to the wilderness, and with tales for friends and family, not all of them tall.

You gotta be a football hero!

Fast forward to high school. My junior year, I joined Stewart, a senior, as a starter on the 1959 Tullahoma High football team. Stewart was team captain, and again, I visualized myself in that role when I was a senior. Our team was 7-0 and ranked number one in the state at mid-season. Unfortunately, we lost two of our last three games, the final one a 26-0 loss to cross-county rivals Manchester. This loss probably cost our team a bid to the prestigious Clinic Bowl in Nashville. On top of that, on the way to the locker room after the game, some of the Manchester players roughed up Stewart, an act that infuriated us all.

Surviving the Sixties

During the late Sixties an era of psychedelic experimentation began during which we tried LSD, peyote, psilocybin, pot, hashish, opium, morning glory seeds and, various other drugs. Our boundaries began to shift and expand, and we started to look at the world, at life differently. Everything we’d been told, everything we’d taken for fact, each of our versions of reality were up for grabs.

Fortunately, Stewart and I avoided being drafted during the Viet Nam War, a military adventure that we considered both immoral and illegal. And with our friends, we took a stand against the war participating in local and national protests.

While Stewart and I didn’t make it to Woodstock, we were at the Atlanta International Pop Festival over the July 4th weekend in 1969 with 150,000 other celebrants. The event took place at a stock car raceway south of Atlanta where there was no shade, and temperatures hovered around 100 degrees. Fire trucks were brought in to spray the crowd, and needless to say, everyone welcomed sundown.

The festival showcased an amazing array of performers, including Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, Chuck Berry, Booker T. and the MGs, Canned Heat, Spirit, The Staple Singers, Joe Cocker, Chicago Transit Authority, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Al Kooper, Led Zeppelin and the Dave Brubeck Trio.

After I moved to Knoxville then to Texas and Stewart settled into Keel Hollow, near Huntsville, Alabama, we saw each other less frequently. However, we stayed in touch with one other, and were deeply grateful to reconnect in Asheville, where we hiked, enjoyed delicious meals at Mela, relived old times, and delighted in the joy and splendor of Rachel and Stephen’s wedding.

So long for now, old friend. Who knows, maybe our paths are destined to cross again one of these days.

Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep

by Mary Elizabeth FryeDo not stand at my grave and weep,

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

I am the soft starlight at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.