My dad and the American Dream

By the time a man realizes that maybe his father was right, he usually has a son who thinks he’s wrong.

~Charles Wadsworth

If you look deeply into the palm of your hand, you will see your parents and all generations of your ancestors. All of them are alive in this moment. Each is present in your body. You are the continuation of each of these people.

~Thich Nhat Hanh

My father, Mack Mulkey, was a member of the “greatest generation.” He and his contemporaries met the challenges of the Great Depression, the rise and fall of the fascist powers, the threat of nuclear war, the Civil Rights movement, the assassination of national leaders, the rise of sexual equality, the Vietnam War, and the resignation of a president in disgrace.

Belief in the American Dream—the opportunity to pull yourself up by your bootstraps and create a better life for you and your family—ran deep in this generation. And given my dad’s roots, he had plenty of room for upward mobility. But Mack had a powerful vision of the life he wanted to create and the way he wanted to live it. And he set about early on to bring what he’d envisioned into being.

Mack was raised by his grandparents. His grandfather, Papaw Clayton, made a living selling his garden produce from a horse-drawn wagon on the streets of Fort Worth, Texas. By the time he was in high school in the late ’30s, Mack was living on his own in Dallas, supporting himself by delivering newspapers.

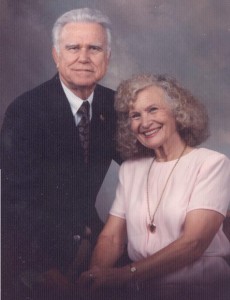

Against the wishes of my mom’s family, Mack and Sue married in 1942, a marriage accelerated by World War II and his impending induction into the Army Signal Corps. And while he served willingly, the young soldier questioned the wisdom of warfare, even the “good war.”

It makes me curse the world and everything in it when I think of the grief that this war is causing. . . . There may be a reason for all of this but I’ll be damned if I can see any sense to it. Maybe, someday the people of the world will wake up and stop all of this nonsense.

–Mack Mulkey in a letter to his wife, Sue, 1944

I became a member of the family in 1943 and my brother and sister were born after the conclusion of the hostilities. Like so many of his comrades in arms, Dad attended college on the G.I. Bill; he earned a B.S. degree in electrical engineering from Southern Methodist University in 1948, the first person in our family to complete college.

Mack’s career path took him from Texas to California to Tennessee. His rise through the ranks to upper level management at Arnold Engineering Development Center in Tullahoma, Tennessee, was noteworthy for a man without an advanced degree. Yet while he resolutely scaled the corporate ladder, he maintained his values and personal integrity, hiring Eddie Harris, the first black man to work at the facility in a position outside janitorial services, in the 1950s.

In the 1960s Mack took a firm stand against the Vietnam War long before it was fashionable. In the early 1970s, he served as the Tennessee state coordinator for Common Cause, a citizens’ lobbying group, “committed to the task of making government at all levels more open, honest and accountable.” And he and my mom remained active in the politics of their community throughout their life together.

Upon accumulating ample financial resources, my dad retired to vegetable gardening, golf, and watching the Atlanta Braves. And he and mom traveled to visit their children and grandchildren.

It was when his interest in gardening began to wane that I knew something was amiss. On November 29, 1996, Mack Mulkey passed away suddenly as a result of the disease he’d had for several years, multiple myeloma. He was seventy-four.

I called him “Daddy” until I was old enough to be self-conscious about what the other kids would think. Later on I settled uneasily into “Dad,” and I began to distance myself from him. But on Fathers’ Day 2002, more than five years after his passing, I have seen him for who he truly was, perhaps for the first time since the two of us played catch on those sweltering summer days in Texas in 1949. Here’s to you, Daddy.

I believe that this is the legacy that you leave us—the ability to open our eyes, our ears, and maybe even our hearts, to those who are different from us–in race, belief, or culture–and that we too can make a difference in the world–by the way we are with others, by taking a stand for what is really important to us, and by having the courage of our convictions.

–From my eulogy for my dad, December 1, 1996