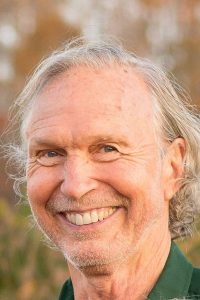

I Turn Three-Quarters of a Century Old Today

Seventy-fucking-five. Three-quarters of a century. Thirty percent of the time the U.S. has existed. In my twenties, seemingly bulletproof and brimming with bravado and condescension, I’d sometimes rail, “Don’t trust anybody over 30.” Anyone in their seventies, in my mind, was ancient and useless. Upon seeing an older man laboriously lumbering down the street, only half in jest, I thought: If I ever look like that, shoot me.

But here I am, confronted with the realization that there are many more years behind me than in front of me, challenged by the fact that the natural aging process is showing up in ways I’d hoped it never would. My hair has transformed from a dirty blonde to almost entirely gray, and while thinning on top, it sprouts from places I’d rather it didn’t, including my ears and nostrils. Though I still check-in at approximately the weight I was in high school, six or seven pounds of it seem to have found a permanent home around my middle. I’ve shrunk two full inches, down now to just under six feet. On the handball court I’m a step or so slower, and I don’t have the stamina I once had for long trail runs. You don’t have to look too closely to see the “turkey-neck” syndrome and bags beneath my eyes. And while I once slept like a baby, I now find myself waking a couple of times each night, frequently with an urgency to urinate (benign enlarged prostate).

Wasn’t it just yesterday that I played handball two or three times a week and, as well, ran the footpaths of the nearby southern Appalachians a couple of times to boot? Didn’t I work twelve to fourteen hours a day for months alongside my twenty-something co-organizers during the 2008 Obama presidential campaign? Was it just my imagination, or didn’t women half my age discreetly flirt with me not so long ago? Weren’t my boys still swimming well enough to father a child when I was in my sixties?

Yes, yes, yes, and yes. But here’s what’s also true. After an arduous workout—handball or otherwise—I require an extra day of recovery to be ready to go again. I now prefer to make my voice heard through my writing rather than knocking on doors and phone banks. Young women (and men) often call me “sir” (an ageist slur to my ears). And, while my sex drive remains quite sufficient with no need for artificial stimulants, pleasures of the flesh are no longer at the top of my consciousness.

The most challenging part of this entire matter, however, is finally confronting my mortality. Spike Milligan’s quotation sums it up for me: “I don’t mind dying. I just don’t want to be there when it happens.” Along with the degradation of our planet, the appalling state of our nation, the fact that I’ve yet to find a literary agent for my memoir, the manner in which our little city of Asheville is being transformed into a tourist mecca without a great deal of consideration for the citizens who live here, Jim consistently beating me in our handball matches, my restless sleep at night—death and dying loom large in the recesses of my consciousness, creating an underlying sense of uneasiness, agitation, and reactivity.

I was reflecting on all this a couple of days ago, when I recalled how I’d dealt with a highly challenging situation a few decades earlier. I was in my forties, working with a relationship counselor with my partner to resolve our differences and, hopefully, get back together. Suddenly, however, without any discussion or warning, she took a job over a thousand miles away and was gone in a matter of weeks. I was dismayed and heartbroken, infuriated and aggrieved. In my mind, this was not the way life was supposed to be. But back in the real world, she was leaving, and there wasn’t a goddamned thing I could do about it.

Miserable and downcast, I cuddled with my trusty cat Chocolate, finding some relief in her resonant purring as she licked my hands and face. Intermittently, however, I felt as though a piece of rusty barbed wire had been inserted through my heart and was being given a hard yank from time to time by some unseen malevolent force. It’s not fair, I thought. This shouldn’t be happening! Then, I remembered a technique I’d learned to help release pent-up anger. I found my old wooden tennis racket, put on my cassette of “Night on Bald Mountain” at full blast, and beat the holy crap out of my couch with the racket while shouting at the top of my lungs: “No, no, no, goddamn it! It’s not fair, it’s not fair, it’s not fair!” I kept at it for five or ten minutes, until I was exhausted and entirely out of breath. Afterwards I felt some relief. The load had been lightened. Given the level of my outrage, however, once was not enough, and I continued this practice every day for several weeks.

When it seemed that I’d fully discharged my rage and resentment, I had an insight: The events in my life were unfolding exactly as they should. If I intended to continue my journey toward living an authentic life and shedding my hypermasculine facade, it was time to let go of a relationship in which my partner seemed to regard my new-found vulnerability as weakness and me, now, as unmanly.

Fast forward to April 23, 2018. So, I located my wooden tennis racket and warned my wife and daughter that I was going to make some noise. I found “Night on Bald Mountain” on Spotify and cranked up the volume. And I whacked the cushions of the futon in our home office with all the force I could muster while yelling, then finally descending into more guttural sounds. I did this for as long as I had the breath to continue. And afterwards, it seemed that the weight of the world had been lifted. I even began to smile a bit and breathe more deeply. Then, one by one, I listened to the lies my internal critic had been telling me—that I’m going to become senile and decrepit, that I’ll be weak and at the mercy of others, that I’ll be ignored and warehoused in a home for the aged, that no one will want to be with me. After a bit of reflection, it was clear that these were all my mind’s projection of the future, a future as yet unknown and unseen.

And what’s true is this: Though I have no idea when my physical demise will come, currently physically healthy and mentally astute, I likely have plenty of good years left—years in which to complete my memoir and share it with the world, years to see my grandkids (now in college) begin their adult lives, years to see my daughter Gracelyn (now seven-years-old) into adulthood, years with my beloved wife Shonnie traversing our favorite mountain trails, and years to work toward a more compassionate, just and sustainable world.

So, I think I’ll follow the path set forth by Ashley Montagu: “The idea is to die young as late as possible.”