My friend Harry Nelson

Harry at the Gerst House in Nashville during the late Sixties

Tuesday night, I awoke from a sound sleep with a powerful sense that something was amiss in the universe. Earlier that day my daughter Lilla had called to let me know that her uncle, my friend and former brother-in-law, Harry Nelson was in hospice, the result of his struggle with leukemia. Wednesday morning, I had a brief text from Lilla informing me that Harry had died during the night.

Though we hadn’t seen much of one another in recent decades, Harry and I, along with others in our merry band of pranksters, experienced the excesses and the turmoil of the Sixties and Seventies together. Just a little older than I am, Harry’s passing has hit me with an unexpected impact, the first of my former intimates to pass (with the exception of Bobby Joe Fisher, who’d taken his life in 1977), providing an unsought opportunity for me to confront my own mortality.

It was during my days as a student at Sewanee that my classmate Harry introduced me to his sister, Shannon Nelson, who would later become my first wife. Right before our wedding, Harry had blown in from D.C. (where he was then living) with a baggie full of potent weed, and I showed up for the ceremony seriously stoned and somewhat apprehensive. Afterwards, some whiskey at John and Frances Nelson’s log home outside of Murfreesboro helped steady my nerves.

Every Thanksgiving at the Nelsons, Harry, me, and our friends would take on Harry’s younger brothers, Johnny and Andrew, and their friends in the Turkey Bowl, a flag football game that included the frequent quaffing of beer and lots of (mostly) good-natured taunting. We older guys won almost every year, except for the year Johnny and Andrew rounded up a bunch of ringers who seriously kicked our ass.

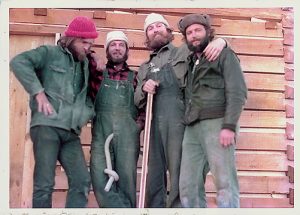

In the mid-1970s, Harry, my brother Art, Bobby Jernigan, and I built a log home for Guy and Candie Carawan, of “We Shall Overcome” fame, on their land adjacent to the Highlander Center, located near New Market, Tennessee, which was around twenty miles outside of Knoxville. In a photo taken during construction, we four all sported long hair and full beards, and Harry had a three-foot long piece of round foam insulation protruding from his fly.

To avoid the daily commute, we sometimes stayed in Highlander’s dorm where we cooked our meals in their commercial kitchen and plucked vegetables from their community garden. When we did make the drive in our trusty pickup trucks, it was coffee on the way to the job and beer on the way back as we listened to Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson and David Allan Coe on the cassette tape player. On Fridays, the four of us knocked off mid-afternoon and played handball at the University of Tennessee courts, mixing up doubles teams each week. After the match, the two on the losing team bought the first pitcher of beer at the Roman Room.

Over time we became friends with the Carawans and their children, Evan and Heather and were sometimes invited to social events at Highlander, which had switched focus from civil rights to worker health and safety issues in the Appalachian coalfields. One night we were there for a potluck dinner and a jam session by Guy, Candee, other folk musicians, and Harry on his brand-new mandolin. That evening Harry, who could have easily been a studio musician in Nashville, performed a dazzling rendition of the mandolin solo in Rod Stewart’s “Maggie May.” Afterwards Harry sidled up to me as we listened to the other musicians and in a low voice said, “Do you ever think this is what we’re really supposed to be doing?” What a turning point might that have been if I’d taken Harry’s question seriously. Why would we want to change anything? I wondered to myself without truly considering Harry’s wisdom. But in retrospect, what if we’d taken the road to political activism and community building when we had the opportunity instead of continuing to eke out a living building a few log homes a year and living an oblivious, hedonistic lifestyle? What if?

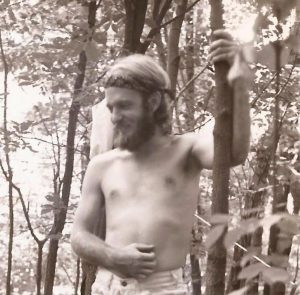

Harry in the early Seventies

As I approached age forty in the early 1980s, the guys in our tightly-knit construction crew, began to go their own ways. Harry married Peggy Nuckolls and moved to the Nelson’s farm in Murfreesboro, where they built a home of their own and started their family. My brother Art remarried and re-enrolled at UT. And Bobby Jernigan left to become a plumber.

Eventually, Shannon and I would also part company, at which point I lost my connection with the Nelsons, Harry included. From then on, I would only see them at Lilla and Brandon’s wedding celebration and the funerals of John and Frances Nelson, the patriarch and matriarch of the clan.

I’ve missed you, Harry Nelson, more than I realized. And I’ll now miss you even more, knowing you’ll no longer be holding down the fort at the Nelson homestead. So, it’s with deep sadness that I conjure up a tad of my three years of French at Sewanee to wish you bon voyage, mon frère.