Two Attempts to Change the Course of Our Nation’s History

One morning a few weeks ago, I was browsing the daily online headlines when I came across an article describing the lengthy prison sentences, ranging from 10 to 22 years, given four Proud Boys. Each had been convicted for playing a major role in the rampage at the U.S. Capitol Building on January 6, 2021 in an attempt to derail the peaceful transfer of power from Donald Trump to Joe Biden. “Fuck around and find out, boys,” I laughed to myself while sipping the last dregs of my coffee.

As I savored the consequences that had been dealt, however, my mind flashed back to another confrontation at a federal building in Washington, D.C., this one over half a century ago.

It was 1969, and the war in Vietnam raged on. I was twenty-six years old and had helped organize the October 15 Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam at Middle Tennessee State University, a day on which anti-war demonstrations took place in cities and on college campuses around the nation. Intent on doing my part to end what I believed was a disastrous, unjustifiable, and immoral war, my then-brother-in-law Johnny and I drove from Tennessee to Washington, D.C. to participate in the second Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam protest on November 15, 1969. We would stay with Harry, Johnny’s older brother (also my then-brother-in-law) at his D.C. apartment.

We arrived too late to join in the March against Death, which began on Thursday evening (November 13) and continued all day Friday (November 14). More than 40,000 people silently paraded single file down Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House. Each marcher carried a placard with the name of a dead American soldier or a destroyed Vietnamese village along with a candle. The march was entirely silent except for six drums tapping out funereal dirges. At the Capitol Building the placards were placed in coffins.

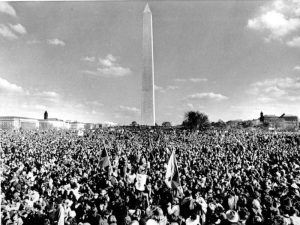

On Saturday, we joined 500,000 demonstrators from across the nation at the Washington Monument. We sang along as Pete Seeger led us in John Lennon’s “Give Peace A Chance.” “All we are saying is give peace a chance” with Pete shouting above the crowd’s chorus, “Are you listening, Nixon?” “Are you listening, Agnew?” “Are you listening at the Pentagon?”

Peter, Paul & Mary performed three tunes including Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are A-Changing,” Arlo Guthrie led us in “This Land Is Your Land,” and Richie Havens gave a rousing rendition of “Freedom.” Other performers included including Earl Scruggs, Leonard Bernstein, Joan Baez, the Cleveland String Quartet, and the touring cast of “Hair.” In addition, Coretta Scott King, Dick Gregory, John Denver, and Senators Eugene McCarthy, George McGovern, and Charles Goodell (a Republican) gave stirring speeches calling for an end to the war.

Johnny and I sang along and chanted with the crowd. “Peace now!” “Hell, no, we won’t go!” Exhilarated to be a part of this extraordinary event, we believed our efforts would change the course of history. After the demonstration concluded, deeply satisfied, heartened and energized, we began walking back to Harry’s apartment, when a group of militant activists cajoled, “Come on, we’re headed to the Justice Department.” Without a second thought, Johnny and I joined in.

When we arrived at the Justice Department, a crowd of around 10,000 demonstrators had gathered in front of the building, separated from a phalanx of policemen in full riot gear by a team of volunteer Moratorium marshals, who were attempting to maintain order. Demonstrators verbally taunted the policemen, but I saw no physical violence taking place. Using a bullhorn, the police demanded that the assembled crowd of demonstrators depart the premises immediately. But before anyone really had an opportunity to respond to their demand, the police set off a massive tear gas attack with clouds of gas that enveloped everyone present.

Coughing and eyes watering, Johnny and I hastily began leaving when police fired a multitude of tear gas cannisters into the air that landed and exploded among the retreating crowd. Though breathing was difficult, I began to run with Johnny hanging onto my right coat sleeve and a woman we didn’t know hanging onto my left. After traveling a hundred yards or so, the woman suddenly released her grip, but Johnny and I continued to run as fast as possible. When we finally broke out of the cloud of tear gas, Johnny told me that the woman who’d been with us went down after being struck in the head by a tear gas canister. “Damn,” I said, “I wish we could’ve helped her.”

When we got to Harry’s place, we shed our tear gas-soaked clothes and showered before recounting our adventure, filled with hope that what we’d done that day would influence Congress and the President to end the war in which 1000 American soldiers were losing their lives each month, as well as additional thousands of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians.

So, two attempts to change the course of history fifty-four years apart: At our nation’s Capital Building on January 6, 2021, protestors attempted to thwart the transfer of the office of the presidency from Donald Trump to Joe Biden. On November 15, 1969, protesters at the Justice Department attempted to compel Richard Nixon to end the war in Vietnam. As I reflected on the differences and the similarities of these events, I pondered: What if the D.C. police hadn’t been present in such overwhelming force? What if the leaders of the demonstration had broken into the Justice Department building? Would I, filled with passion and righteousness, have been caught up in the herd mentality? Would I have entered the Justice Department Building and desecrated the offices and their contents? Would I have believed such actions were fully justified in a noble attempt to end the war?

I wonder.

Postscript

While we had hoped that our massive turnout and the growing public opposition to the war would bring the politicians to their senses, we saw little immediate evidence of such an effect. The war would rage on until 1975 resulting in the total deaths of 58,220 American troops and the additional deaths of approximately 200,000 South Vietnamese soldiers, 1,100,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters, and 2,000,000 civilians on both sides.

What we wouldn’t know until the release of declassified documents by the National Security Archive in 2015, however, is that our massive efforts for peace did have an effect. After receiving reports of the enormous crowd at the protest on November 15, 1969, Nixon reluctantly called off his irrational plan for a major escalation of the war against North Vietnam, including the use of tactical nuclear weapons, an action that could have provoked the Chinese or Soviets to enter the conflict with nuclear weapons of their own and set off World War lll.