Loving, sensitive, trusting, and curious when I entered life in 1943, at around five years of age, in reaction to the disparaging remarks and denigrating actions by the mostly well-meaning adults around me, I unconsciously began to believe I was unlovable, inadequate, somehow inherently flawed.

Little boys don’t do it like that!

Let your grub stop your mouth!

Stop that whining or I’ll give you something to whine about!

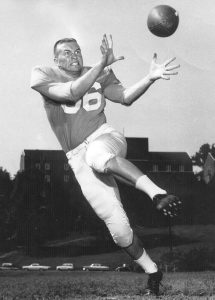

To conceal my increasing sense of shame and self-consciousness, I gradually fashioned a protective façade—an emotionally constrained, tough, and devil-may-care persona modeled on the stoic demeanors of John Wayne (“Never apologize, mister. It’s a sign of weakness.”) and other heroes of the silver screen in that era. And over time, I perfected the drama, forging myself into a hyper-masculine super-jock whose nascent sense of self-worth was bolstered by the admiration of fellow students, teachers, townspeople, and college football coaches.

Regrettably, I subsisted beneath my macho persona for so long that I came to believe I really was the hard-ass who regarded women, people of color, and members of the working class as inconsequential characters in my personal drama. However, beneath my seemingly impervious veneer, I lived in constant subconscious fear of being exposed as a fraud, and it was essential that I save face at all costs. Whenever anyone even hinted at a chink in my defensive armor, I often reacted with fury and, sometimes, my fists. (“Screw with me, shithead, and I will kick your ass!”) From all outward appearances, I might have seemed the master of my domain, but beneath my tough guy facade, there was a scared young boy.

Some think of Donald Trump as a real man, someone who tells it like it is, who rails against political correctness, who pugnaciously stands up to his opponents, who goes for the win at all costs. But I’m very familiar with his macho man routine. If you delve beneath his defensive armor, you’ll find a frightened little boy, one who never admits a shortcoming of any kind, one who takes no responsibility for his actions, one who relies on the adulation of his followers to boost his shaky self-esteem.

In Mary Trump’s book Too Much and Never Enough, it’s clear that Donald Trump’s father, Fred Trump, ruled his family with an iron hand and abhorred any sign of weakness in his brood. From that experience, the author states, “He (Trump) has to need to prove to be tough, to be a killer” and “not to be weak and not to apologize.” But his outer toughness merely masks the obvious: Deep down inside Trump believes he is weak, unworthy, less than others. And thus, it’s imperative that he scorn any show of empathy, openheartedness, or other emotion that might be judged as unmanly.

I’ve sometimes wondered how a large percentage of voters in this nation can still support Donald Trump’s reelection after all he has said and done. But the unfortunate truth is that Trump has tapped into the unconscious fears of many American men about their own manhood, about their ability to adequately care for their families, about losing their place in the pecking order, a position based on the white male supremacy on which this nation was founded.

It’s clear to me that no amount of rational conversation, no amount of factual data will convince Trump supporters that he is not worthy of the office. Trump channels their outrage toward those who challenge their entitlement. We will not change their deep-seated beliefs that create their fears; they can only do that themselves. My vision for the future of this nation is that this strain of toxic masculinity will continue its decline as old white men pass away and younger, more self-aware men take their place. And then, hopefully, the world will be a better place for all of us, men included.