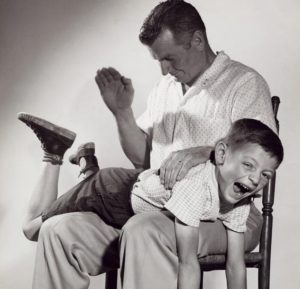

Spanking gets results . . . just not those you’re likely to desire.

My great-grandmother, Mae McCarthy (better known as Ma), who enjoyed dipping snuff and preferred another layer of body powder to regular bathing, had a Victorian attitude when it came to disciplining children. On a warm afternoon in June when I was four, I watched with dismay as Ma instructed Mom in how to choose a good switch from the limbs of a flowering bush in the backyard. “You want to get a stout branch that won’t break when you swat him on his legs and little heinie,” Ma said. “Always remember the old saying, ‘Spare the rod, spoil the child.'”

I wasn’t spanked frequently, but when physical punishment occurred, it was usually because Mom had grown so frustrated and angry with my recalcitrance or noncompliance that she merely did to me what had been done to her when she was a child. I don’t recall that Dad ever resorted to spanking me. Mom’s belief was that spankings would teach me to toe the line, obey her directives, and teach me right from wrong. In retrospect, what I think Mom unconsciously desired was not discipline, but domination and control, so that, to make her life easier, I’d do exactly what she wanted when she wanted me to do it.

When I was around twelve or thirteen, however, Mom flew off the handle about something my younger brother Butch and I had done, and she advanced toward us down the hallway with one of Dad’s belts raised for action. As she lunged forward to strike me, I grabbed her arm that held the belt with one hand and wrestled the belt free with my other hand. Momentarily bewildered at the reversal of control, she collected her wits and shouted furiously, “Just wait till your father gets home!” Dad got home, nothing happened, and that was the end of the spanking at our house, at least as far as I was involved.

During each of my three years of junior high and my first year of high school I probably averaged two to three paddlings (as corporal punishment by the principal was called) each year. Each paddling consisted of five to ten licks (the number of times one was struck, which depended on the severity of the offense), punishment primarily for wise cracks at a teacher’s expense, practical jokes, skipping school, or rough housing. I wore these occasions of corporal punishment as badges of honor, walking out of the principal’s office with a smirk on my face regardless of how much I’d actually been hurt physically or humiliated emotionally. In fact, the boy (it was always a boy) who had gotten the most licks at the end of the school year was considered something of a celebrity. At the end of my eighth grade year, the honor was mine with twenty-six licks.

Spanking sucks because science.

That was the 1950s. But even now in the U.S. approximately two-thirds of parents still believe spanking is a necessary and effective way to discipline a child. This, of course, flies in the face of scientific studies that show that corporal punishment is totally ineffective and is, indeed, quite damaging. In fact, more than forty countries, most of them in Europe and South America, have outlawed corporal punishment of children in any setting, including home and school. In 2006, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child called for the elimination of all “legalized violence against children.” Only the United States and Somalia failed to ratify the treaty that established the committee while one-hundred-ninety-two countries supported it.

What does today’s science say about corporal punishment? Eighty-eight studies of more than 36,000 individuals show that non-abusive corporal punishment of children can lead to aggressive and delinquent behavior, and such punishment can break the bond of trust and weaken relationships between parent (or other adult) and child. Later in life, adults who received this type of punishment are more likely to experience a higher rate of depression, anxiety and drug dependency, as well as being more likely to abuse their child or spouse. Scientific studies also show a negative correlation between spanking and a child’s IQ and the amount of gray matter in that child’s brain. What’s more, research shows that though parents who use spanking may get immediate fear-based compliance with their demand, the message about the unacceptable behavior they are trying to squelch is typically lost on the child they are striking.

Yeah, yeah, I know, you were spanked as a child and you turned out OK. But what if you hadn’t had to tamp down your enthusiasm, candor, liveliness, and other authentic behaviors for fear of arousing the ire of whatever adult happened to be in charge? Isn’t it possible you might be living your life with greater joy, purpose, connection, and creativity if you hadn’t been subjected to the pain and humiliation of physical violence by people several times your size?

What I learned from being spanked.

Let me tell you what I learned from adults in my life who endeavored to impose their will on me through corporal punishment.

I did not learn respect for the elders who hit me; in fact I felt increased emotional detachment and, thus, less of an inclination to follow their lead in the future.

I did not learn to follow the inconsistent, unjust, and sometimes absurd rules and conventions put forth by the adults in my life, though I’d pretend to, surreptitiously waiting to ridicule them (and their rules) whenever the opportunity arose.

I did not learn to submit to authority figures; I learned to push back against oppressive and hurtful behavior in any form.

I did not learn to settle differences and conflicts in a mature and mutually agreeable manner; I learned that I was justified in using violence (frequently my fists or foul language) to get my point across.

I’m pretty damned sure those weren’t the results the adults in my life were going for.

* * *

When parents resort to spanking their child, perhaps they’re merely parenting as they were parented. Rather than placing all the blame on the child for upsets or conflict in the family, regardless of whether the child is judged to be obstinate, disobedient, or insubordinate, perhaps we as parents might take a few deep breaths and look at how we helped create the situation before taking an action that could produce some of the negative consequences mentioned above and which might later be deeply regretted. Perhaps it’s finally time to let go of such old paradigm disciplinary techniques and to learn more effective parenting skills, methods that honor both parent and child.

[This essay originally appeared at The Good Men Project.]